LET US NOT BE OVERCOME BY THE EVIL BUT OVERCOME EVIL WITH GOOD!

Saint Paul – Romans 12:21

NAM TUA RES AGITUR, PARIES CUM PROXIMUS ARDET –

YOU TOO ARE IN DANGER, WHEN YOUR NEIGHBOUR’S HOUSE IS ON FIRE – HORACE

Inside for subscribers: “I need to disappoint you. All parties are ONE SOLID mechanism. They are handled from one single purse, but by different cashiers. The struggle between those is just a show. Some say for the cattle, some for the sheep, some for donkeys… Depends where you come from… The corridor is defined by the CONCEPTUAL POWER. Shows how to move and how to punish those who jumped out of it! That is why we have the saying that the laws are only for enemies!“

To most of us the world is a jumbled mass of conflicting and confusing ideologies without rhyme or reason or purpose. At philosophyofgoodnews, with every click you will be going into adventure, pursuing the truth. We want to leave an impact and make the world a better place. we want to fight all those mercenary pens who propagate the methods instructed by the organizers of the destruction of our earth and universal family values. Open your defense mechanisms to get a simple truth! As Henry Ford SAID:

“THE TRUTH FREQUENTLY IS DEPRESSING; THE TRUTH SOMETIMES SEEMS TO BE EVIL; BUT IT HAS ETERNAL ADVANTAGE, IT IS THE TRUTH, AND WHAT IS BUILT THEREON NEITHER BRINGS NOR YIELDS TO CONFUSION.“

NAVIGATION

WORLD VIEW; DAILY PROMPT; WORLD NEWS; “DUSTY” BOOK CLUB; PERSONAL STORIES; CONSPIRACY PRACTITIONERS; HOW TO LEARN TO STUDY QUARANTINE DIARIES AND BEYOND – eBOOK; FAITH, HOPE, LOVE; QUARANTINE DIARIES; DRILL BABY, DRILL; SANE OR INSANE; COMMON SENSE; PHILOSOPHYOFGOODNEWS QUOTES

CONTACT US FOR ANY QUERIES YOU HAVE

TRENDING

-

Iran bombs Dubai….

Just received this one Fairmont Hotel, the Palm Dubai Things are getting serous…. February 28, 2026 Philosophyofgoodnews.com Connect and Respect

-

It started… USA started bombing Iran

Just got this video showing Iranians missile hitting something in Abu Dhabi… One day earlier than projected. OUR MARCH 1ST PROJECTION STORY! However, expecting the president to talk on March 1st. When I say March 1st, I mean in any time zone… Until then, let’s hope that this madness will stop! But one is certain. The…

-

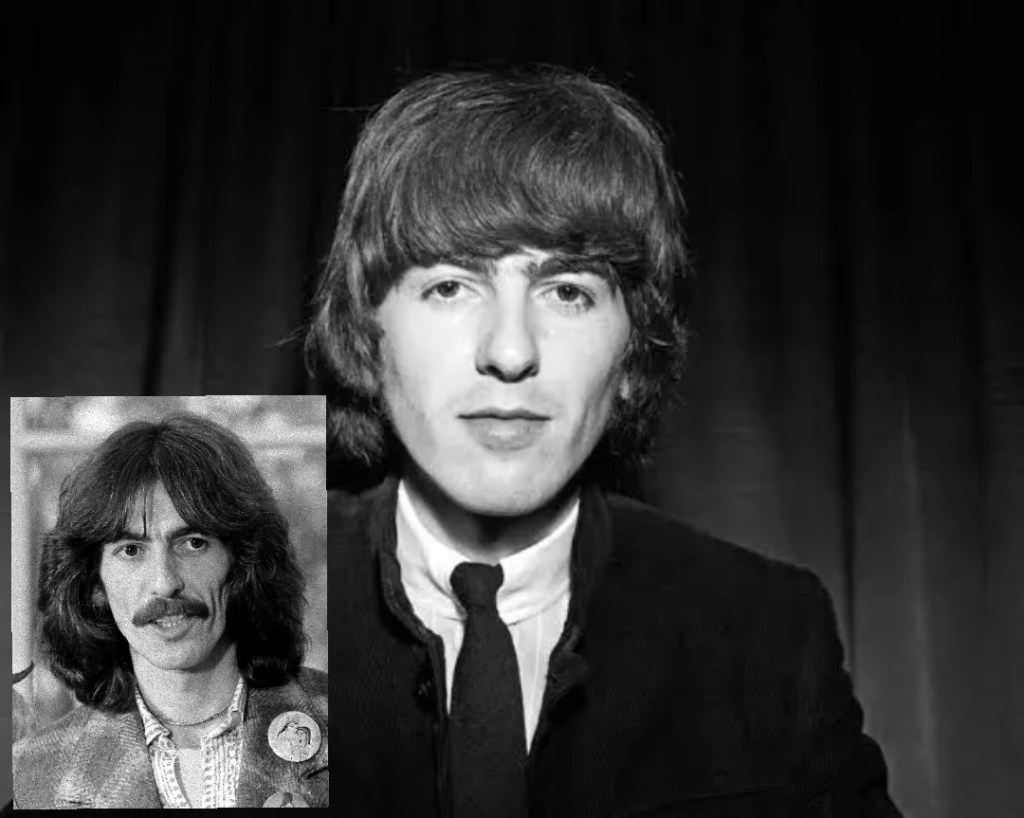

As yesterday, George Harrison was born in 1943

HERE COMES THE SUN! George Harrison, the guitarist of Beatles, was born on Ferbruary 25, 1943. Today, he would be 83 years old. He left us when he was 58, showing that it is not how long you live but what you leave behind you. George Harrison left so many beautiful songs behind that all…

-

Guardian of positive, human memories

What advice would you give to your teenage self? I must be honest and completely truthful. Contrary to what great G.K. Chesterton said about the program of public schools. He mentioned it’s utterly blatant and indecent disregard of the duty of telling the truth. He also referred to a blinding network of news phraseology that…

-

March 1st, 2026

If something happens, it will happen on March 1st. Until then, a lot of blah blah blah will continue. Of course, preparations will continue with the Americans listening and Iranians counter-listening… And with Russia mingling with China… The EU —– What EU? Serious issues inside Iran universities will escalate. This shows that education based on Western…

-

“Board Of Peace”

Deception or not, that is the question. Genuinely or not, that is another question. Is there a universal right of someone to displace people under any pretext? Well that is for you to reply. What philosophyofgoodnews can offer is to give some history, as history has already been written. First is the poem of legendary…

-

Let’s make it clear

Are you patriotic? What does being patriotic mean to you? I think that all of us humans should be patriotic. It is a feeling of being useful to your family to your people, to your country. In all you do, in every word you speak or write, in every move you make. Now we come…

-

Philosophyofgoodnews Quotes February 19, 2026

Well, this is more like a statement Missing somebody? CALL Wanna meet up? INVITE Wanna be understood? EXPLAIN Have questions? ASK Don’t like something? SAY IT Like something? STATE IT Wanna something? ASK FOR IT Love someone? TELL THEM KEEP YOUR LIFE SIMPLE, AND YOU WILL FIND HAPPINESS EVERYWHERE! Prepared by Darko Richard Lancelot Philosophyofgoodnews…

-

President of Serbia writes: AI Summit places India at the centre of the global discourse

“Animated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambition to democratise access to the benefits of new technology, the summit seeks to ensure that AI is not the preserve of a privileged few.” Source: President of Serbia writes: AI Summit places India at the centre of the global discourse Prepeared by Darko Richard Lancelot Philosophyofgoodnews Connect and…

-

Blind and Deaf?

Are we still both blind and deaf? If yes, even partially, let me share a quote from 1957. It was expressed by the “lecturer” of those who planned today’s ongoing events. However, it looks like their influence and power are diminishing.. They shake and shake. They cause new wars and do not end old wars.…

-

Philosophyofgoodnews Quotes February 17, 2026

“In the hands of a skilful indoctrinator, the average student not only thinks what the indoctrinator wants him to think . . . but is altogether positive that he has arrived at his position by independent intellectual exertion. This man is outraged by the suggestion that he is the flesh-and-blood tribute to the success of…

-

Again and Again and Again, the same stupid mistakes by the same circles

In 2010, Angela Merkel had serious policy disagreements with then British PM David Cameron about banking regulations, etc. I wrote then that a powerhouse of Europe, Germany, is again being played. I said, poor Germans will be the victims of their leadership, their deep state, again. Actually, Germany accepted the bait, seeing it as an…

-

The Date Of Templars is Passing. Number 5 is approaching in March

February 18, 2026 addition! February 20 is another day that would satisfy the symbolic! Simply because it is 2+2+2+2+6=”14 = 1+4=5 Again 1+4=5 That will be the message of power towards humanity. Below is the previous post ——————————————————– I will not analyze number 5 here. Subscribers received the full report on number 5. What is…

-

Remember

You get some great, amazingly fantastic news. What’s the first thing you do? I must share this! It is not if I got some great, fantastic, amazing news, no. I have a strong opinion that WE create that news! Absolutely. We work and live. We talk to the world and do things. We inspire and…

-

Trump ‘insisted’ to Netanyahu that Iran talks continue as Israel pushes for tougher limits

If true, that shows that there is some other power beyond financial one. That subtle power is quiet but very decisive. What is it? EXISTENCE! You put it wherever you think it is appropriate… “Trump says the deal needs bans on nuclear weapons and missiles. Netanyahu’s office says he wants tougher limits, including on missiles…

-

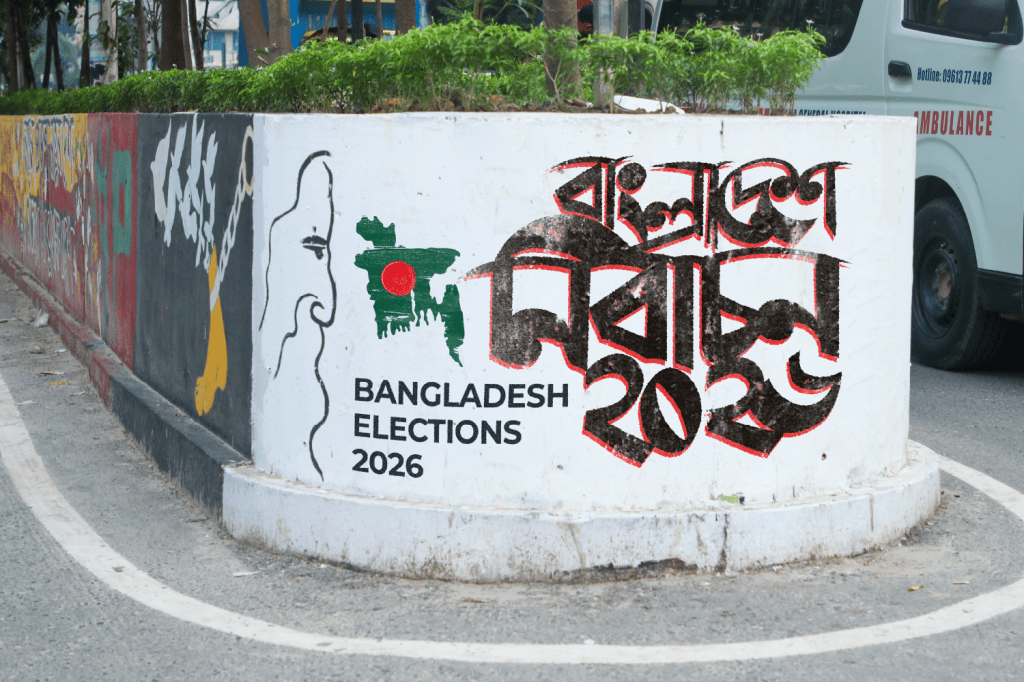

Bangladesh election 2026 LIVE updates: Tarique Rahman, Yunus cast vote; Hasina’s stronghold sees low voter turnout

One of the countries with huge potential for growth and progress. Hope these elections will bring people who are patriots and have a vision for Bangladesh to become a strong, progressive place open to investment. You can follow the link as it is LIVE news! “Bangladesh election LIVE updates: Voting is currently underway in Bangladesh’s…

-

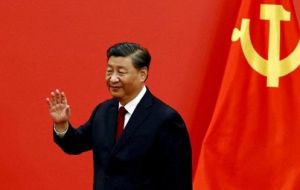

China’s Xi calls to make Renminbi “a powerful currency,” as Trump is ready to change Fed’s chair

Following the statement of President Xi Jinping things will never be the same. As he stated, China is the world’s second-largest economy. He continued that China is the industrial giant, the technological giant, and the economic giant. Not a financial giant. Now that comes in front! But he says that the financial system will be…

-

US-IRAN GO TO WAR ON FRIDAY THE 13TH?

I am not an analyst in the way of all those we see on YouTube and around. But we humans can feel and read between the lines. We can follow the numbers and analyze characters and their interactions. Here is why I connected it. We have two days left, and as Benjy is in the…

-

Who is Mrinank Sharma? AI expert who left Anthropic and issued a chilling warning, predicts that ‘world in…’

Another human consciousness reacting and warning! Message is clear! Do not be lazy and become stupid by not using your own brain! Do you get it? If not GET IT NOW! This site is doing it all tbe time. Not convinced? The link to another warning that philosophyofgoodnews shared recently is below WARNING! Now about…

-

Protected: How is the world governed? Subscriber content

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

-

Revenge of Ludik, Lev, Ian Robert Maxwell?

When, in 1997, I first read Jeffrey Archer’s book “The Fourth Estate,” I was amazed. He described two personalities that were fierce competitors in publishing and news businesses. Rupert Murdoch and Ian Robert Maxwell. He, for the sake of the book, “baptized” them Keith Townsend and Richard Armstrong. An impressive story that showed how childhood…

-

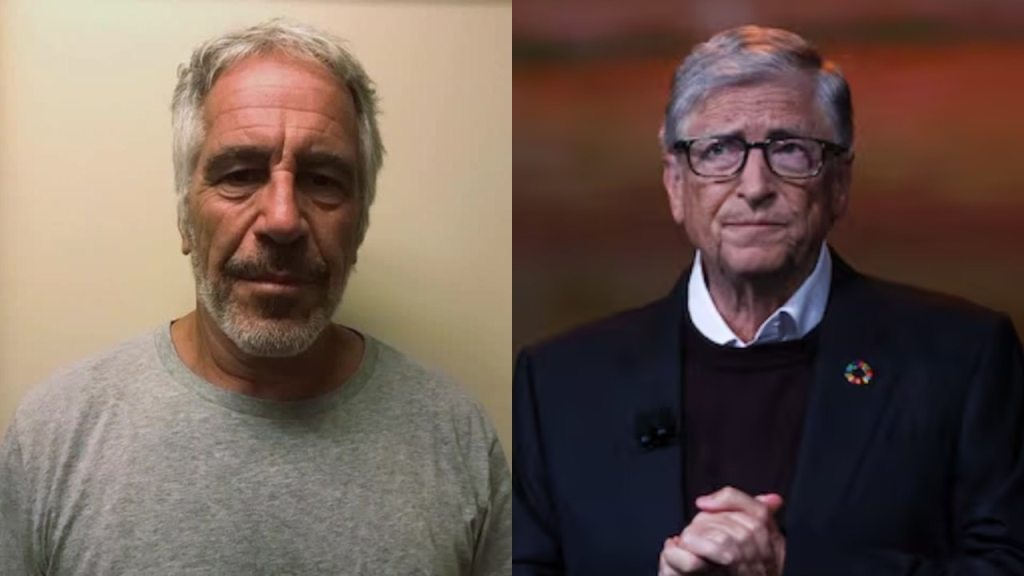

“Ghislaine Maxwell’s prison routine revealed in new video released in Epstein files dump”

More revelations are coming every day. Tomorrow we will publish some history about Ghislaine father, the great man Ian Robert. It will drown out the noise and balance the powerful, blinding light. This will enable you to clearly understand the logic for long-duration operations… It is for subscribers only. “When the video was taken, Ghislaine…

-

“PIGS BALL…”

The title is the translation of the French edition of one book. In light of these Epstein files that are being carefully thrown at us, the public, one book comes to mind. It is not YET translated into English, maybe because of the serious pressure from the special hidden breeds… Those that carefully choose “The…

-

Melinda Gates says ex Bill Gates needs to answer Epstein questions

And one more mail: Opportunities… If anyone knows, is Madame Melinda. She was married to this man on the left side of the picture for 27 years… She is a hero! “Melinda French Gates says ex-husband Bill Gates needs to answer for his connection to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and the allegations in the…

-

Bill Gates, Russian girl, case of STD, and a closer look at Epstein emails casting shadow on tech biggies

Is this possible? Come on, the guy is messiah for many! You know those “trust science not morons.” Oh, sorry if you were one of those. It is ok to be manipulated but it is a tragedy to keep it as you was right. Continue reading by visiting the source. “It looks like no one…

-

Who is Earl Anthony Wayne? Ex-US Ambassador To Mexico Accused Of Raping 11-Year-Old Girl In Epstein Files

So, one asks if this is possible? “Earl Anthony Wayne is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center. “Tony,” as he is known, is also a distinguished diplomat in residence and professorial lecturer at American University’s School of International Service and advisory board co-chair of the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute.” This site…

-

Sharing Dear Friend Thoughts

What do you complain about the most? Sharing thoughts of one of my dear friends! “For half a century, I have lived in a world where there is no good and no bad.This world taught me to be a witness, not to be a side.This geography silence, my family patience, my workplace belongingness… Through it…

-

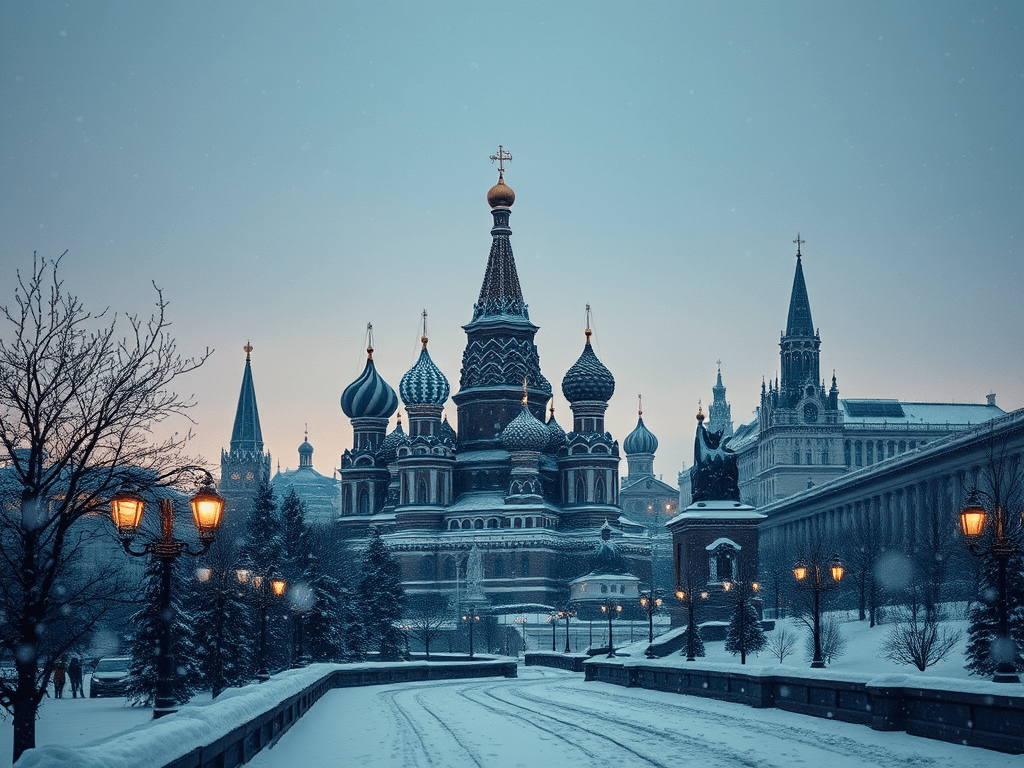

Putin meets with top Iranian security chief — RT Russia & Former Soviet Union

As propaganda works overtime it is important to report the truth. That Iranian government plane that came to Moscow did not carry Iranian President, but Mr. Ali Larijani. Message from the supreme leader has been conveyed… Lets see where will this take the world. Whatever, the world is rapidly changing, and hope we stay alive…

-

Moscow greets foreign leaders…and awaits…

Snow is falling in Moscow. A romantic atmosphere was awaiting the leaders of Syria and the UAE. Coincidence? President Trump just shared that he kindly asked President Putin to stop bombing Ukraine for a week. The temperatures there are expected to reach -26 Celsius! Coincidence? Moscow (Kremlin) issued an invitation to Zelenskyy. He was invited…

-

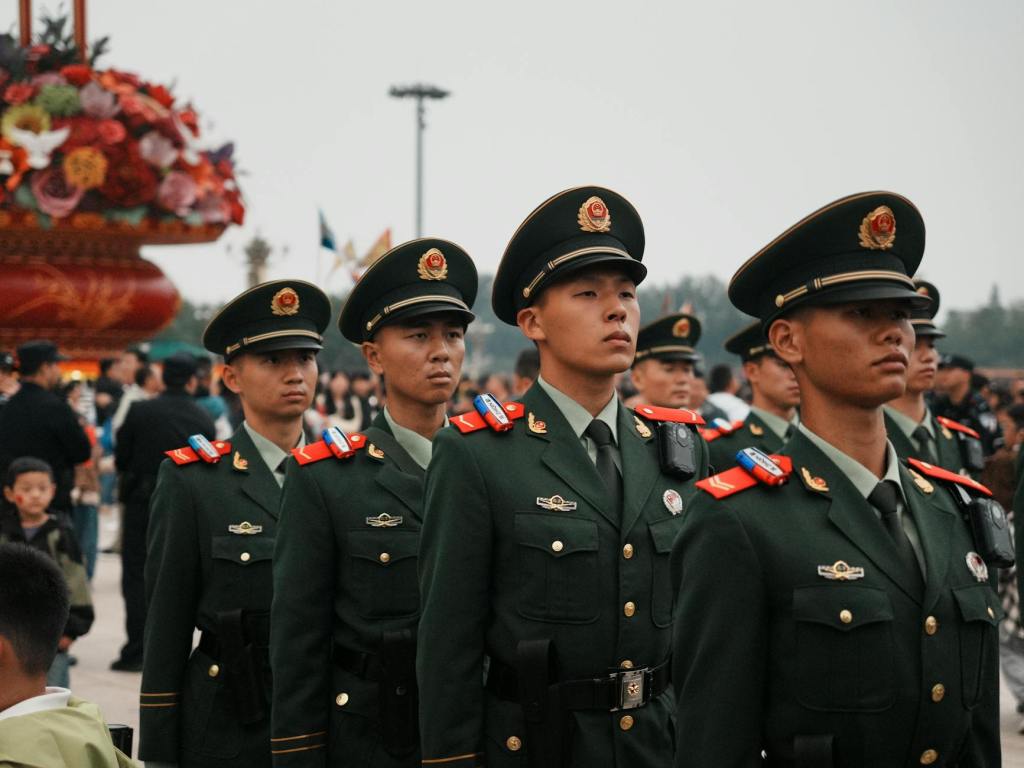

Why China’s Military Leadership Is Being Reshaped

President Xi is consolidating power, preparing China for the global leadership. For that to proceed filling the holes that many rats did is a MUST! China wants to pursue an independent amd sovereign policies based on WIN – WIN strategy! And that policy is giving results. It was well known that President Xi made enemy…

-

Bangladesh’s economic roadmap: Priorities for the next government

Very interesting development for Bangladesh’s future. Two important parts will need to be addressed. One involves educating young Bangladeshi in foreign countries. Another involves placing skilled workers abroad. With their remittances, these workers will help balance the current account. At the same time Bangladeshi garment industry, specialized in the CMT business, will continue to grow.…

-

Hungarian Prime Minister Orban Replies to an Insult

It happened some days ago, but still, it is important to be reposted! It was a reply to insult, saying that Victor Orban “deserves a slap in the face.” “Dear President Zelenskyy,It seems to me that we will not be able to come to an understanding. I am a free man who serves the Hungarian…

-

Questions

List five things you do for fun. Some are playing cards, some are running, and some are swimming. Some are making TIKTOK or INSTAGRAM stories and reels, some are doing something else. I ask questions! What? Oh, that’s the first question! We live in a world where everything is questionable. On so many occasions, questions…

-

Following the news – Lab Grown Meat

I just read reports that at this 2026, Davos forum so-called elites “push for lab grown meat!” They are in rush? Of yes, ask yourself why? So-called elites push for the so-called lab grown meat. First thing that came to mind is that they are a perfect match! The so-called elites can illuminate themselves with…

-

U.S. envoys meet Putin in Moscow for Ukraine peace talks

After Davos, Moscow. And in Moscow things are going well. Slowly well. For now… New face from the US side reported… Joshua Gruenbaum. Who is he? As reported by John Helmer, “Gruenbaum, 39, a law and business school graduate in New York, used to be a salesman for takeover and restructuring of stressed assets at…

-

Greenland, USA, and the world

We want Greenland, is the summary of yesterday’s President Trump’s speech at Davos 2026. “It is, therefore, a core national security interest of the United States of America. And in fact, it’s been our policy for hundreds of years to prevent outside threats from entering our hemisphere….” He started with: “Would you like me to…

-

Short video – Greenland explained down to the small intestine!

-

Davos 2026 Compared Continuation

Please see my “Davos 2026 Compared” post of yesterday before starting this one. One is certain! Each man is his own profoundest mystery! However, there are times when the mystery is explained, clarified, understood, and known. Not to all, but to those who see the details Today, we had President Trump giving his speech. Long…

-

Davos 2026 Compared

In 1976 Davos World Economic Forum was created. It was the year when the equation of 31.1 gr of gold = 35 $ cease to exist! And today, one ounce of gold is? Who is robbing whom? It was the year when the $ lost its gold standard, but due to US great patriots managed…

-

Trump insists on taking Greenland as Europe shuffles responses: ‘The World is not secure unless we have Complete and Total Control of Greenland’

This site was awaiting further developments. Here they are, and the upcoming event at Davos will confirm it. President Trump is going there with a huge delegation. He will deliver a speech that will outline many things, including Greenland. It will confirm and reveal other aspects as well… As Dmitry Peskov, President Putin’s press secretary,…

-

“I Want You To Do It!”

Before letting you know where this title comes from let me share a short thought. It looks like this is the war between White and Black Karma. Israel attacked first picking the Black Karma. Iran reaction picked the White Karma. That is how the future will develop. Another interesting thing is that the Benjamin was the…

-

November 21, 2024 – “You will fight, We will win.”

Those causing this mess that is taking us towards NUCLEAR ARMAGEDDON can not command their wishes from their office, like Boris Johnson did in April 2022! They also can not do so from deep underground. If they want to win, they should go into the fight. That includes their family and friends, too. All of…

Want to share news?